|

The Library

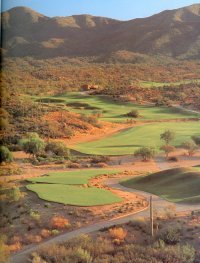

Chapter 1: The Playing Field Golf Course Settings Parkland Courses When the courses moved inland from the sea and began to be carved out of North American woods and forests, the first parkland-style courses were created. Trees are an integral part of the playing challenge. On the plus side, they act as perceptual guides for the players. But they also can be penal hazards, which force you to take additional strokes and incur penalties. They also obscure vision and hide other features of a course. Courses cut from heavy tree stands have a “chute” feeling. Keeping your driver in the bag is often sound strategy. Grasses frequently are heavy and lush, often providing good lies in the fairway. On the downside, because of clay soil, more moisture, and sodden turf, you tend to get less roll, especially in the rough. Fairways frequently are sweeping, with a rolling character. You can use these contours to your advantage. On the other hand, rolling slopes force you to consider intended landing areas carefully because shots frequently finish on sidehill angles or roll into unforeseen difficulties. Gauging roll accurately is important - unless you’re proficient swinging on one foot or enjoy chipping out of trouble. One significant factor on a parkland course is the character of the wind, which is usually a zephyr, as contrasted with a gusty seaside breeze. When the woods are cleared to create fairways, some pockets are left that amplify and redirect the wind with a boomerang effect, causing it to swirl and making it difficult to judge distance and determine ball movement along a flight path. When such winds are present, be extra careful to evaluate their force and effect. One trick is to scan the tops of trees for movement. Sometimes you can’t feel it, and other times it comes from a totally unexpected direction. Desert Courses At one time, deserts were perceived as poor sites for golf courses. But new irrigation, earth-moving, and maintenance techniques now give designers more options. Topographically speaking, deserts are predominately level but can feature noticeable elevation changes when located near mountains. A prime example is the Mountain Course at the La Quinta Hotel Golf Club near Palm Springs, California. While the site is mainly flat, many holes are nestled against mountains and offer deceptive uphill and downhill transitions not normally associated with desert courses. Areas of inland California, the Southwest, and Florida have similar terrain. Surprisingly, Florida has many courses with desert characteristics, such as little variation in topography combined with sandy soil. One such desert locale was the Royal Rabat course in Morocco, where my father and I had an experience that illustrates the theory of attack and defend as it relates to the construction of a golf course. The site was an army encampment, so we were asked to give a briefing to the soldiers, who were going to build the King’s course. We were taken into a tent where out routing plans had been hung on a board, as if they were sketches for a military campaign. In effect, they were, because the plan encapsulated our defensive strategies for the course. When playing a desert course, be aware that designers often work overtime creating features in these settings. For example, nonindigenous grasses for fairways and greens are specified by the designer; lakes are also manufactured for visual contrast and improved aesthetics. In some cases, designers go to extremes to relieve flatness by creating elevations, including mounds that offer both obstructions and crazy caroms.

Desert fairways and greens have two common characteristics. Due to the sandy composition of the soil, the conditions of both these areas are very firm. Additionally, the intense sunlight combined with today’s irrigation systems allows for a healthy growth of turf grass, which can be tightly manicured. Together, these factors result in extra bounce and roll, thus increasing distance. However, the extra roll can make your short-game and recovery play more difficult, due to reduced control in stopping the ball on the greens. In states like Arizona, where water for irrigation is at a premium and governmental limitations on the amount of playable acreage are present, designers are often forced into creating tight, narrow courses. These constraints are heightened by the fact that desert rough and transition areas are difficult to recover from. In this regard a desert course mirrors a links in that areas off the fairway contain native vegetation. Additional fieldwork is required to discover which growths are playable (avoid the jumping chorocactus). Those who ignore this advice are destined to lose strokes, clubs, or clothing. Desert courses are sometimes situated on rising plateaus near the foothills of mountain ranges. Frequently, coyotes think they’re members. In addition to dramatic backdrops, these arid mountains offer the designer options for creating contour, elevation, and perception puzzles. Errant shots will often find rock outcroppings and reptiles as well. Mountain Courses

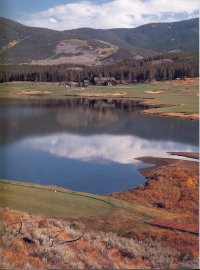

Mountain courses feature dramatic change in elevation and often give players the feeling of negotiating a slalom course. Like a testy hill, these courses are exhilarating but require precision and clear thinking. If you get too caught up in the scenery, disaster is inevitable. Because of the topography, many holes are routed through narrow canyons, and accuracy is a must. Don’t hesitate to sacrifice yardage for direction. It’s easier to take a lesser club than hunt for an errant 300-yard drive. Mountains mean water, often twisting, crystalline streams. Most designers try to integrate them into the routing. Occasionally, streams will be difficult to see, so check the scorecard for maps. At the course I designed in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, the rushing Fish Creek comes into play on many holes, acting as a perilous water motif. Situated at heights, mountain courses can produce a loss of balance, a sort of golfing vertigo. This reaction may be subtle but can affect club selection. The added elevation means thinner air and shortness of breath. Shots will travel farther. The rule of thumb is 2 percent for every 1,000 feet of elevation, but, it possible, test this rule on the practice range before you play. Probably the most critical factor in playing a mountain course is deception: things are not as they seem. At my father’s El Rincón Club in Bogotá, Columbia, and my design in Keystone, Colorado, distances and dimensions seem quite different at elevations of approximately 9,000 feet. You can be sure the designer of a mountain course will use this perceptual difference to his advantage. Again, be aware of these potentially deceptive features, and see if you can solve their mysteries on the practice range before you start your round. Tropical Courses Tropical courses are something I know well, and I’ve got the insect bites to prove it. I’ve worked on more than twenty-five tropical sites, from the Caribbean islands to the jungles of Mexico, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific. Unlike desert environments, where there is a sparse vegetation and trees, the forests and jungles pose opposite problems for designers and golfers. In many tropical areas, particularly the islands of the Caribbean, Hawaii, and the South Pacific, trade winds affect the design of holes.

Many jungles grow on mountains, so courses built here combine mountain and jungle environments. For example, at our Four Seasons Resort course on the island of Nevis in the Caribbean, errant shots end up in jungle ravines bordering fairways. On the courses I’ve done in Malaysia and the Philippines, what I call “edges” (the natural areas just off the fairway) would be easier to attack with a machete than a 5-iron and offer practically no hope of recovery. Accuracy is mandatory unless you like snakes. Jungle environments conceal dangerous obstacles that magnify the challenge and excitement. You never know what you’ll encounter. At Royal Selangor Golf Club in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, wild monkeys have sometimes chases gofers. In certain areas, various reptiles reside in the foliage adjacent to tees and greens. On some courses in Asia you’ll find a local rule that provides: “A player may remove a ball two club lengths from a coiled cobra or sleeping tiger without penalty of death.” He may also run like a scared jackrabbit. Maintenance on tropical courses is often difficult, so be prepared to play in less than perfect conditions. Grass can grow uncontrollably and sporadically in these regions, causing a variety of lies. As you can see, golf courses have many faces, depending on where they are built. To succeed on a particular course, you must know the territory and its specific conditions, and adjust your game plan accordingly. Now let’s go to the first tee, where your round begins.

|