|

The Library

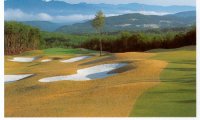

Chapter 1: The Playing Field Golf has a playing field like no other in the world. Mountaineers, hunters, fishermen, trekkers, cyclists, and scuba divers may command the most extensive locales in which to pursue their challenges, but among the games that require a formal playing field, golf offers an unusual combination of rigid specifications mixed with sometimes wild and unpredictable irregularities of nature. In other words, no two courses or rounds are ever so alike that you can attack them with exactly the same game plan. For me, the constantly changing conditions and the infinite variety of holes define the essence of the game.

One way to understand how a designer envisions a course is to look at other sporting activities. For example, when I design a course, I have in mind chess, pool, auto racing, and certain target sports. Chess Chess is intrinsically a game of attack and defend. Like chess, golf is a silent battle - give or take a few eruptions - in which the architect assumes the role of defender against the golfer attacking the course. Imagine a well-defended golf hole as a giant chessboard where the designer has created a system of defenses. They can be as obvious as a waste bunker or as subtle as a mound or a contour in a putting surface. The designer not only places obstacles on a hole but also may camouflage them. A good rule for playing golf then, is to start each hole aware that there may be subtle, mysterious or even hidden elements waiting to sabotage your game. Your attack on a hole involves land and air strikes. From a land perspective, visualize yourself threading a path through the defenses in search of the best landing and takeoff areas, much the way ground troops move from position to position when assaulting an enemy fortification. Obviously, attacking a hole by air is a major weapon in your arsenal. Be aware also that designers employ illusion, prevailing wind currents, and landscape to challenge your attack. Simply getting the ball into the air isn’t enough if it lands in the wrong place. Thinking about golf as a giant chess game played between designer and golfer will help you understand the need for long and short-range strategies. Chess masters are great because they have a custom-made strategy for each opponent. You need the same for each hole and each course. If you think the pros play a different game, you’re right. They ask numerous strategic questions before they see a new course and often rely on caddies to scout the most subtle nuances. Practice rounds are used to probe the design, and holes are analyzed shot by shot after each round. Nick Faldo of England and Bernhard Langer of Germany are two outstanding professionals who leave nothing to chance. Faldo walks the course without clubs to study its characteristics, while oftentimes Langer measures every hole with a yardage wheel to get exact calculations to and from features before hitting a practice shot. Pool Golf is colloquially referred to as “pasture pool.” Pool proficiency requires mastery of spins and angles and skill in organizing a sequence of shots. Winning depends heavily on sound, strategic thinking. Champion pool players, such as Minnesota Fats or Steve Mizerak, know how to manipulate the cue ball with spin. Their wizardry includes almost perfect control of all angles on a pool table. Golf is also a game of spins and angles. Pros talk of “working” the ball. Technically, this means imparting various spins so that while the ball is airborne it moves toward the chosen target and rolls advantageously when it lands. Working includes the skills of fading, drawing, stopping the ball, and making shots bounce forward. While a well-made pool table is a perfectly planed surface, a golf hole can be seen as a field of hundreds of angled planes, which can deflect the ball in various directions. Visualize a hole as a series of planes without grass, trees, and water. That’s the designer’s view when he lays out a hole. Like pool, golf is primarily a game of position. The professional pool player never takes one shot at a time. He organizes a series of shots in his mind in order to sink all the balls on the table. The key is to get a good “leave,” or an ideal position for the next shot.

During the Greater Ozarks Open at the Highland Springs Country Club in Springfield, Missouri, I was paired in the pro-am with professional Bob Lunn and three other amateurs. On the 430-yard par-4 seventh hole, a dogleg left around a large lake, Lunn played close to the water and attacked the flagstick with no fear of the lake. I drove down the right side of the fairway, taking the water out of play. One of my playing partners, a stocky fellow with a healthy handicap, attempted to follow Lunn’s route. He wound up wet. Auto Racing Golf is similar to auto racing in several ways. All top drivers have heroic courage and a special talent for shifting gears to match the racecourse. Indianapolis 500 winner Danny Sullivan, an avid golfer, noted the parallels during an AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am. “I look for the curves and banks on a golf course the way I do when I drive a race car,” he said. “If you aren’t aware of them, they can ruin your day.” A golf hole starts out like a straightaway, with the golfer flooring it (swinging aggressively) on most par-4s and par-5s for distance. Then he downshifts (approach shot), eases up on the accelerator for a hairpin turn (chip), and guides the car (ball) across the finish line (into the hole). It’s an ongoing adventure to get the most from your car or clubs without pushing too hard. If players are not mentally conditioned, they will fail to master the course. Venues like the U.S. Open are the ultimate test of patience and perseverance. When Tony Jacklin won the 1970 U.S. Open at Hazeltine National in Minnesota, friends taped the word TEMPO on his locker before the final round. Despite slick greens, thick rough, and windy conditions, Jacklin was able to adjust his game and maintain composure throughout the five-hour ordeal. All pros know that rhythm and positive thinking are essential to winning. Just ask their sports psychologist. On certain holes, a designer may attempt to upset a golfer’s balance and mindset. He tempts you to push too hard or take unnecessary chances. I often say, “Lost ball, lost stroke, lost confidence.” Target Sports A final comparison can be made with target sports. To understand target golf, we must examine the evolution of shot making. Golf started as a knockabout affair in which players advanced the ball with a stick toward an endpoint, the early game being played mostly on the ground. Technical advances in ball construction, club making, and swing mechanics produced a higher shot trajectory, and the game moved from a land campaign to an aerial assault. The consequences have been twofold. First, golfers today watch pros shoot “darts” from great distances and often believe that is the only way to play the game. Second, on many modern courses, targeted areas have been designed and maintained to receive high-trajectory shots. Someday golfers may enjoy even greater distances, although its hard to imagine anyone hitting a ball farther than John Daly. When astronaut Alan Shephard hit his famous shot on the moon on February 5, 1971, Walter Cronkite of CBS television said, “Soon, we’ll have a Robert Trent Jones course on the moon for Alan to play.” If I ever get to build it, we’ll name it Moonscape Golf Course and it will play about 40,000 yards from the back tees. That should keep Daly on his toes. One way to view a golf hole is as a series of defined target areas. In the illustration of the 520-yard par-5 second hole at Wailea’s Gold Course on Maui, Hawaii , I have taken a par-5 hole and out-lined archery-like bull’s eyes in various spots. With your tee shot you can aim for a reasonably large landing area, say 20 to 30 yards in diameter, whereas hitting into the green from 100 yards, you should be trying for an area 20 to 30 feet in diameter. I encourage every golfer to consider separating some holes into a series of par-3s to better visualize the hole as a group of distinct targets. Note the diagram of the par-4 hole. Player A sees a 250- yard par-3 and a 140-yard par-3, while Player B sees a 200 yard par-3 and a 190 yard par-3. Each player proceeds with a specific target in mind on each stroke, and the prudent golfer will avoid trouble and play within his ability level. This approach played a key role in Raymond Floyd’s victory at the 1986 U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills Golf Club in Southampton, New York. At the 513-yard par-5 sixteenth hole, Floyd played two accurate shots to intermediate targets and left himself in perfect shape for a short iron to the green - on of his strengths. Floyd made a birdie and clinched the championship, becoming the oldest U.S. Open winner, which proves that position and smarts can often outwit length and youth.

|